Key Points:

- Although using a partial range of motion allows you to add more weight to the bar, this often results in a decrease in training volume, since you are decreasing the distance the bar travels (see Volume definition below).

- Using a partial range of motion can keep constant tension on the muscle, if the range of motion is restricted to the “mid-range” of the exercise. That said, there is limited evidence that this results in greater hypertrophy.

- Even if we assume that all IFBB pros use partials, this form of evidence should not outweigh the results of scientific studies.

- Of the six studies available on the topic, only one supported that using a partial range of motion is superior for muscle growth.

- As a general rule of thumb, training with a full range of motion will likely result in greater muscle growth compared to using a partial range of motion. That said, partials may have a place as an advanced technique for some isolation exercises and for maximizing strength on certain compound lifts (e.g. bench press and deadlift).

Key Terms:

- Range of Motion: The distance and direction a joint can move within its inherent potential

- Partials: Reps using a partial range of motion

- Volume: Often calculated as Reps x Sets x Weight. However, this assumes a constant range of motion, so, for our purposes, it should be calculated as Reps x Sets x Weight x Distance, where distance is the percentage of the range of motion performed.

- Isolation Exercise: An exercise that only works one muscle group (e.g. bicep curls, calf raises)

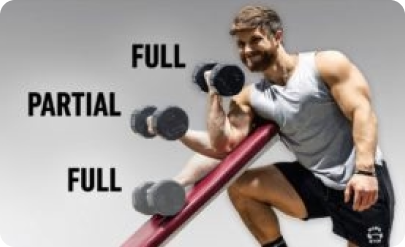

Simply put, range of motion refers to the distance and direction a joint can move within its inherent potential. Training with a full range of motion then, implies you go through the full movement potential for a given exercise. In contrast, training with a partial range of motion indicates that you compromise the range of movement, falling short of its maximum range.

From what I’ve seen, most people tend to fall neatly into one of two camps: the “Science Camp” or the “Bro Camp.” People in the Science Camp generally argue that a full range of motion is better for muscle growth and, for the most part, partial reps are really just ego reps.

Undoubtedly, some of you likely find yourselves agreeing more with the Bro Camp and prefer the use of partial reps for one of three reasons:

- They allow you to move more weight.

- They permit you to keep constant tension on the muscle by keeping the weight in the so-called “mid-range.”

- Many IFBB pro bodybuilders use partials and they’ve achieved better gains than all of us.

Up front, I think both sides have some valid points. But, the question remains, “Which side has it more right?”

As we tackle this question head on, let’s start with the three main arguments coming from what we have referred to as the “Bro Camp.”

1.PARTIALS ALLOW YOU TO MOVE MORE WEIGHT, RESULTING IN MORE TENSION ON THE MUSCLE?

Although you will be able to load more weight when you cut the range of motion short, this doesn’t mean you’re putting more tension on the muscle. The extra weight is coming at a cost; as you increase the weight, you’re simultaneously decreasing the distance that weight is moving.

To illustrate, let’s say you currently squat 225 lbs (or two plates per side) for three sets of eight reps. You decide to cut the range in half, which allows you to squat three plates per side. On the surface, it might look like you’re handling more total workload. In reality though, you are actually handling significantly less!

225 x 3 sets x 8 reps x 1 distance = 5,400 lbs of volume

315 x 3 sets x 8 reps x 0.5 distance = 3,780 lbs of volume

As the math above clarifies, doing 225 pounds for three sets of eight reps would net 5,400 pounds of volume. That said, when we calculate workload, distance is assumed to be constant. So, if we decide to jack the weight up to 315 pounds by cutting the range of motion in half, we also have to cut our workload in half. Therefore, from a hypertrophic standpoint, that increase in weight simply isn’t worth the tradeoff in distance.

As you can see, the Bro Camp’s first argument isn’t their strongest. Trading range of motion for weight is almost always a bad trade. However, there may be a few legitimate exceptions that we’ll get to later.

2. PARTIALS CAN ALLOW YOU TO MAINTAIN CONSTANT TENSION ON THE MUSCLE?

In my opinion, this second argument from the Bro Camp is much stronger. While it may sound nearly identical to the previous argument, it differs in that, rather than just cutting the range of motion in half (e.g. lowering the bar only half way to your chest during a bench press), the constant tension advocates tend to stop just shy of full lockout by cutting out the top and bottom of each rep. Their idea here is that if you fully lock out a rep, your muscle gets a little “mini-rest”and briefly loses tension in between reps. This may not be ideal for growth.

In fact, one 2017 study supports that hypothesis [1]. Researchers compared doing skull crushers through a full range of motion to doing skull crushers through a half range of motion, restricted to the middle part of the lift. The full range group would then be getting a little “tension break” at the top of each rep, whereas the partial group would have the triceps engaged from start-to-finish throughout the set. After eight weeks of controlled training, they found significantly better muscle growth in the partial group (nearly twice the gains by keeping constant tension) – and these were decently well-trained subjects.

While this study did have its limitations (eg. the partial group may have just been getting closer to failure), I still think it lends some support to the bros’ argument for constant tension – at least on certain movements. On exercises like skull crushers and dumbbell flyes, where the top part of the range is fairly easy, I think it makes sense to stop slightly shy of full lockout. It seems, however, that this advantage is most likely limited to free weight isolation exercises and probably wouldn’t apply as well to exercises that use cables and machines, since they automatically provide constant tension for the most part. You can see then, that here it makes more sense to instead emphasize a full stretch and a full squeeze.

Before we get too excited about this single study, I should point out that of the six studies we currently have on range of motion and hypertrophy, this is in fact the only one that favored using a partial range of motion [1-6]. Again, this is likely because a single-joint free weight isolation exercise like the skull crusher is uniquely benefitted by constant tension when compared to other exercises.

Before we return to the other studies, let’s address the final argument from the bro camp.

3. IFBB PRO BODYBUILDERS USE PARTIALS

To begin, I’m not entirely sure that statement is completely accurate. At least in the classic era (i.e. around the time of Arnold and Ed Corney), it was very common to see the top pros using a full range of motion on a variety of different exercises.

That said, I know a lot of modern day pros who do seem to favor partials, so let’s just assume it is true that most IFBB pros today prefer to do partials over a full range of motion. Still, the problem is that these bodybuilding anecdotes simply lack the rigor and control of scientific studies. In other words, it’s really hard to say if these bodybuilders are getting their results from partials specifically, or from some other training variable, or from great genetics, or because of their nutrition, or supplementation.

Now, I don’t think these anecdotes are worthless. I’m actually open to the idea that partials are better for this population, but I also think that when making recommendations, if there’s stronger, better evidence available (which there is in this case), these anecdotes should be taken with something of a grain of salt. So, let’s take a closer look at what science really has to say about range of motion and muscle growth.

From the Mouth of Science

Earlier this year, a systematic review was published examining all the studies that we currently have regarding range of motion and muscle growth [7].

Now, we aren’t going to go through all six studies in detail, but the bottom line is that all four lower body studies found that a full range of motion was better [2-5], and the upper body studies gave conflicting results [1, 6]. One of the upper body studies found no difference between doing full range curls and “active tension curls” and the other was the skull crusher study we just discussed – again, the only one out of six to actually favor partials.

Taken together then, I think we have good enough evidence to say that a full range of motion is usually better for muscle growth, especially for the legs. Consider this one study from Bloomquist and colleagues where they compared heavier partial squats to lighter deep squats and, despite being lighter, the deep squats still caused much more muscle growth at every site across the entire quadricep [2].

Overall, I think the best rule of thumb is to use a full range of motion most of the time by getting a reasonably full stretch at the bottom and a reasonably full contraction at the top. But, this doesn’t need to be taken to the extreme either; there’s no benefit to pushing your range of motion beyond your comfortable limits. For example, some people’s skeletons simply won’t let them squat ultra-deep without tons of lower back rounding. So, when deciding what full range of motion means, it is important to keep your own mobility in mind and avoid the “more is always better” trap.

In fact, a recent MASS piece pointed out that as long as you actually get to the hardest part of a lift, you’re probably maximizing the hypertrophic effects. Furthermore, since squats tend to be hardest at around parallel, squatting to just below parallel is probably nearly as good (or just as good) as squatting ass-to-grass for quad growth.

What Are The Exceptions to The Full ROM Rule?

There are also a few exceptions to the full range rule:

First of all, I think it does make sense to use partials as an advanced technique on some isolation exercises where you simply cut out the bottom or top part of the range, where it starts to feel really easy. For example, I’ll often cut out the bottom of dumbbell lateral raises, because there’s no tension on the delt down there. Similarly, I usually don’t fully lockout skull crushers or dumbbell flyes for the same reason. I also think it’s smart for more advanced trainees to do some extended sets on isolation exercises for stubborn body parts, where you extend the set beyond failure by doing partials after exhausting your ability to do a full range of motion – especially if it’s your last set for that muscle. Of course, this shouldn’t make up the majority of your program, but it can have its place as an exception to the full range rule.

Second, the bench press and deadlift may also be an exception for some powerlifters or power-builders since the goal isn’t merely to maximize growth, but to also move the maximum weight within the guidelines of the sport. Because of this, I personally use a powerlifting-style arch on my bench press, despite the fact that this will limit my range of motion to some extent. However, when you compare joint angles between an arched bench and a flat bench, there’s actually not THAT much of a range of motion difference anyway. So, this is a fair tradeoff for me, especially once you consider that the bench press isn’t the ONLY exercise I do for my chest. I can make up for any minor “range of motion-deficit” by simply combining exercises.

I also make a similar exception for the deadlift, where it’s a smarter powerlifting strategy for me to use a sumo stance, even if it limits range of motion slightly. And again, because I still hit the hardest part of the lift, the hypertrophic implications are likely negligible; especially once you consider that I’ll be combining different exercises for these muscles anyway.

So, perhaps unsurprisingly, I do find myself more on the science-side of this debate. I think that as a general rule of thumb, training with a full range of motion all the time will get you better results than training through a partial range of motion all the time. Luckily, in the real world, though, our advice doesn’t have to be quite that black and white. I think we’ll get our best results when we borrow the best of the wisdom both sides have to offer.

References:

- Goto M, Maeda C, Hirayama T, Terada S, Nirengi S, Kurosawa Y, Nagano A, Hamaoka T. Partial Range of Motion Exercise Is Effective for Facilitating Muscle Hypertrophy and Function Through Sustained Intramuscular Hypoxia in Young Trained Men. J Strength Cond Res. 2019 May;33(5):1286-1294. [PubMed]

- Bloomquist K, Langberg H, Karlsen S, Madsgaard S, Boesen M, Raastad T. Effect of range of motion in heavy load squatting on muscle and tendon adaptations. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2013 Aug;113(8):2133-42. [PubMed]

- McMahon GE, Morse CI, Burden A, Winwood K, Onambélé GL. Impact of range of motion during ecologically valid resistance training protocols on muscle size, subcutaneous fat, and strength. J Strength Cond Res. 2014 Jan;28(1):245-55. [PubMed]

- Valamatos MJ, Tavares F, Santos RM, Veloso AP, Mil-Homens P. Influence of full range of motion vs. equalized partial range of motion training on muscle architecture and mechanical properties. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2018 Sep;118(9):1969-1983. [PubMed]

- Kubo K, Ikebukuro T, Yata H. Effects of squat training with different depths on lower limb muscle volumes. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2019 Sep;119(9):1933-1942. [PubMed]

- Pinto RS, Gomes N, Radaelli R, Botton CE, Brown LE, Bottaro M. Effect of range of motion on muscle strength and thickness. J Strength Cond Res. 2012 Aug;26(8):2140-5. [PubMed]

- Schoenfeld BJ, Grgic J. Effects of range of motion on muscle development during resistance training interventions: A systematic review. SAGE Open Med. 2020 Jan 21;8:2050312120901559. [PubMed]